- Home

- Katherine Sparrow

Little Apocalypse Page 2

Little Apocalypse Read online

Page 2

The sad boy walked closer to Celia, putting himself between her and the others. He placed his hands on his hips. “This is private property.” He spoke with a soft accent. Russian, maybe.

“I know,” Celia said. “I live here.”

“This is a private meeting.” He crossed his arms over his chest.

“But . . . what are you doing up on the roof? Are you in some kind of trouble? Can I help?”

One of the kids peeked out from behind the pipes. Dark curly hair sprang from her hood. She had some kind of birthmark on her face. “That’s her! The girl from my dreams.” The words echoed across the roof.

Celia shivered and stood up straighter. “You dreamed about me?”

The girl grinned and nodded.

Celia smiled back. It didn’t seem possible that someone she didn’t know would dream about her, but she liked it anyway.

“Shut up, Daisy.” The sad boy stepped between them so Celia couldn’t see the other girl. “It’s not safe up here,” the boy said to Celia. “We’re just here because . . . we’re kids whose parents aren’t home. We’re having a meeting about it and it’s private.”

“Really?” Celia grinned and bounced on the tips of her toes. “My parents aren’t home either,” she said, before realizing a second later that she had just broken a rule. “So does one of you live here?”

He nodded and kicked the gravelly ground. “I do.”

“You must be new. Apartment 7G, right?” Celia asked.

“Yeah.”

“Cool,” Celia said, except now she knew he was lying—none of the apartments in the building had letters. She took a step closer and a smell wafted off him, like apple pie and . . . sunlight? That wasn’t right, but it was as close as she could get to describing it. “So what are you all doing? I can hold hands and chant with the best of them.” There was something about the earthquake and the weirdness of tonight that made Celia feel like she could make friends with them. It had been a long time since she’d even bothered trying.

A panicked look covered the boy’s face. He shook his head. “I’m sorry. You can’t—”

“She could help us! We could all become friends and do stuff together,” a boy’s voice called out from behind the pipes.

“I’d like that,” Celia said quickly.

“No!” the sad boy said. He stepped away from her. “No. You have to leave right now.”

Celia swallowed over a lump in her throat. Why do I even try? She wondered. Why did I even think for one second that anyone could like me?

“It’s not you,” the boy added. Gentleness filled his voice. “But you do have to go.”

“Fine.” Celia bit her lip. “I’m gone already.” She turned to go, but stopped when she got to the door. “What’s your name?” she called back. “In case I see you later?”

“You won’t. I’m . . . Demetri.” His face had long shadows and dark pits for eyes.

“I’m Celia. I live right below here.” She pointed to the part of the roof that was her bedroom’s ceiling.

Celia turned and walked away from them. Something strange was going on up here. Something that involved a group of poorly dressed kids, yo-yoing, and a middle-of-the-night rooftop meeting. But whatever it was, she wasn’t invited.

Back in her apartment she listened to their footsteps overhead and the rhythm of various sirens going off across the city. It felt like she would never fall asleep.

3

Everything Is Only Going to Get Worse

Celia woke to morning light. The earthquake’s wreckage surrounded her, and everything looked worse than she’d imagined. She tried not to stare at the deep cracks in the ceiling’s plaster. She tiptoed around the broken things and tried both phones again. Neither worked. Her laptop would turn on, but there was no Wi-Fi. She dug out an old battery-powered radio from the camping gear in the back of the hall closet and found a station where a reporter listed what buildings had collapsed, and the names of the twelve people who had died. Celia switched stations and listened to a scientist explain that an earthquake in Youngstown meant there was some as-yet-undiscovered plate tectonic activity beneath the world’s surface.

Celia found a brown paper bag and began picking up pieces of broken glass off the kitchen counter, careful not to cut her fingers.

The mayor came on the radio and said both bridges into the city had been wrecked, and for the moment there was no way to drive on or off the island. Help was coming, the mayor said in her clear, strong voice. Emergency workers would be arriving on trawlers, as soon as the docks were fixed. Aid would get flown in, once the airport runway got repaired. “Stay home and stay safe. Everything will go back to normal in a day or two.”

Celia imagined her mom at her grandma’s, and her dad in a hotel room, both trying to find a way to reach her. She imagined them worrying and wished, more than anything, that she could hear their voices and tell them she was fine. It felt like if she could tell them that, then she would be fine and the jittery-sick feeling running through her would go away.

Celia poured a bowl of raisin bran, cut up a banana, and opened the fridge. Milk and vegetables tumbled out. The refrigerator had a rotten smell. She rescued the milk carton from the floor and poured some into her bowl. The slightly warm milk tasted gross. Celia leaned against the kitchen counter and ate the cereal until it was all gone.

In the bathroom, she automatically tried to flip on the lights. Nothing. Celia tried to call her parents again. Neither phone worked, same as before.

She was just wondering what she should do next when her apartment started to shake again. Another earthquake? An aftershock? But before she could run to the kitchen table and duck beneath it, it stopped. Then started. Then stopped again. It came from the ceiling. Something massive and heavy was stomping around on the roof.

Were those kids still up there? Celia wondered. She hadn’t heard them walking around for a while. Were they okay? Maybe I should go up and check, she thought, not that they would be anything but annoyed by that. Before she could make any decision, someone pounded on her door. Celia ran to it and peered out through the spy hole. Demetri stood on the other side, staring back.

12. Celia will not hang out with strangers.

But did Demetri count as a stranger? She’d met him already, and he was just a boy her age who was probably here because he wanted to apologize for being so rude last night. Maybe he’d been freaked out and now he wanted to say sorry, Celia thought. She decided her parents would like her hanging out with someone her own age, and probably didn’t care that much about rule number twelve anyway.

She unlocked the dead bolt, the chain lock, and the normal lock.

As soon as she cracked the door open, Demetri rushed in and slammed it shut. Dark moons ringed his eyes and his skin looked pale and sweaty. Had he slept? His scent of apples and—sunlight? Yep, same as last night—filled the room.

Celia inhaled the lush scent. “What’s going—”

“Shhh.” He locked all the locks on the door, then ran into her living room. He pulled the blue curtains closed over the bay windows, and the light in the apartment turned from morning bright to underwater blue. Demetri grabbed something from his pocket and tossed it on the floor in front of the windows. When she looked closer, Celia saw it was a handful of robin-blue eggshells.

“What are you doing?” she called out quietly.

Demetri tugged his knotty knit cap down lower on his forehead and wiped sweat from his brow. “Morning, Celia.” He spoke softly. Carefully. For a moment their eyes met and he smiled, but then he looked down at the carpet. “I’m sorry I’m here. I needed to hide, and this was the closest place.”

“Make yourself at home,” she said. “Run inside my apartment and throw eggshells on my carpet. It’s cool and not weird at all.”

Demetri frowned and bit his lip. He looked toward the door, then at the window. “Sorry, but can you keep it down?”

Celia opened her mouth to speak. Something stomped hard on the

roof. It shook the whole apartment. A second later there was a shrieking cry that sounded like a bird. Celia folded her arms over her chest and glared at Demetri. “What’s out there?” she whispered.

“Nothing good.” Demetri tried to smile. “But it’s nothing to worry about, really,” he whispered. “This was the closest place I could find to hide. I’ll leave soon, I promise.” He took out his yo-yo and did a couple of tricks, letting it dance at the end of the string before jerking it back up to his hand.

Celia looked at her front door and then up at her ceiling. Cracks ran across the plaster that hadn’t been there yesterday. What would it take for her ceiling to cave in?

“Are your friends safe?”

He shrugged. “Hope so. They left hours ago. I was finishing up something when I got spotted.” He rocked back on his heels and looked around. He wore threadbare pants, and his hoodie had a bunch of patches sewn on it to hold it together. His fingernails were black. Not dirty, but painted. “So, it’s a nice place you’ve got here, it’s real—”

Celia folded her arms in front of her. “What were you finishing up?”

“Um . . . a magic spell?” He walked to the wall where all the framed photos hung crookedly from the earthquake. He started straightening them.

Celia rolled her eyes. “To keep away the unicorns on the roof?”

Demetri looked confused. “There’s no such thing as—”

“Exactly. What were you really doing?” She walked closer to him.

He stumbled backward from her with a wild look on his face, like she had been about to attack him. He moved so that the big blue love seat was between them. He seemed . . . scared of her?

“You know, last night wasn’t the first time I’ve seen you,” she said. “I saw you four months ago, when I first moved here. You were acting strange then, too.”

“What was I doing?” Demetri walked to the curtains and peered outside.

“You were sitting on a curb, throwing shoelaces into the drain and looking, I don’t know, sad?”

Demetri blinked a couple of times and moved farther away from her. He shook his head. “Most people don’t notice me.” He stared at her like she was something he didn’t understand.

“What were you doing?” Celia whispered.

“More spells. To hide from old ladies and . . . kids like you.”

Rude. But he said it so softly, like he was choosing each word carefully and wasn’t trying to be mean.

The room shook as the thing on the roof stomped around. Celia sank down onto the edge of the orange couch, careful not to step on the broken bowl and gunky chunks of macaroni strewn across the floor. She couldn’t tell if she liked Demetri or not, but she was glad to not be alone right now.

Demetri peeked out the window again, then drummed his hands on the back of the love seat. “So . . . um, what school do you go to?” He spoke like he didn’t know how to ask a question like that, as though he didn’t live in a world where people constantly asked boring questions. He bent down and picked up a fallen framed picture. Behind the broken glass was a picture of Celia, age five and fearless, with pigtails and a rainbow T-shirt. Demetri stared at it intensely.

“Hamilton Middle. You?”

“I don’t. I’m . . . homeschooled.” He put the picture back up on the wall, then bent down and picked up another one. This photo showed a sunny day at the beach with her grandpa, a year before he’d died. Demetri ran a finger over the cracked glass surface.

“Oh.” Homeschooled. Maybe that explained why he and the other kids had been on the roof? Maybe they’d had some assignment to break into an apartment building right after an earthquake and act mysterious? Nope. It explained nothing. And anyway, was he even telling the truth?

“I’ve heard that homeschooling is hard because you have to do two hours of PE a day,” she lied.

Demetri picked another picture up off the floor and put it on the mantel. “Yeah.”

“And it has to be two hours of parkour, where you run around the city and jump off things,” she added.

He started to nod and then gave her a look. “That’s not true, is it?”

“It’s as true as most of the things you’re telling me,” she replied. “Do you always lie so much?”

“I usually don’t talk to people. I’ve . . . seen you around too. I’m not homeschooled, but I do study things. I watch the city, and I’ve seen you walking to and from school.” He hesitated. “It’s not your fault that you’re lonely.”

The thing on the roof made another thump, and the entire living room shook. Celia stared at the ceiling. How did he know she was lonely? Was it so obvious that everyone who saw her knew? “What do you mean it’s not my fault?” Her voice wobbled and she bit her lip. She wanted so much for his words to be true.

Demetri sighed and sat down on the other end of the couch, as far from Celia as possible. He picked up a thick red pillow and placed it between them. “The fact that you don’t fit in here? That’s a good thing. There’s a lot wrong in Youngstown, and even if people don’t know what’s going on, it twists them. It’s not their fault, but it’s not your fault, either. A lot of them don’t know how to be nice to anyone.” Demetri spoke like everything he said was a simple truth. “They’ve been hurt, even if they don’t know how.”

The idea that maybe there wasn’t anything wrong with her felt like a five-hundred-pound weight pressing down on her shoulders had suddenly lifted. Then again, his words didn’t make sense. “Are you lying right now?”

“No.”

Celia stared at him for a long moment. She believed him. Or—she believed that he thought he was telling the truth. “You’re a weird one, Demetri.”

“Yes.”

“Are you hungry? You want some cereal?”

He flinched, even though there was no thump overhead. “Please don’t offer me things.”

“Right. Because you don’t want girl cooties?”

He blinked and looked confused. “That’s a . . . joke?”

“Not a funny one, I guess.”

He tried to smile.

Something boomed overhead.

Celia hid her shaking hands in her lap. “What’s up there?”

“It will be gone soon.”

“If you don’t tell me what’s up there, I’ll have to go take a look,” she said.

His eyes widened. “You wouldn’t.”

“You don’t know me.”

“I do not.” His gaze flicked toward her, then away. “But trust me, Celia. You don’t want to meet what’s on the roof right now.”

“Can I guess? Is it a flock of humongous migrating birds?”

Demetri put another pillow between them. It was the embroidered one with a peace symbol that Celia’s grandma had made.

“A rival gang of kids who walk in formation? A traveling dance troupe?”

Demetri frowned as the thing on the roof thumped around. Puffs of plaster wafted down from the ceiling.

“A construction crew making repairs? A really angry football player?” Celia spoke faster. The longer it stomped up there, the more Celia felt like this wasn’t going to end well. “Am I even close?”

“No.”

“But it’s going to go away, right?” Whatever it was, and nothing she could think of seemed even a little likely, it had to go away. And soon her parents would be back and everything would be fine, right? She really, really wished the thing thumping around up there would stop. “Everything is going to go back to normal—that’s what the mayor said.” Celia’s voice sounded fluttery and small.

Demetri folded his hands over his chest. “Everything is only going to get worse.”

“What?” Celia began picking up broken shards of pottery off the carpet. She laid them in a row on the coffee table. “Why do you think that?”

Demetri didn’t answer. He stood and began pacing back and forth along the length of the living room, taking a zigzaggy route to avoid all the fallen things scattered across the floor.

/> “I’ll leave soon,” he whispered. “I won’t bring trouble here again.” He stopped and picked up two fallen hardcover books that Celia had read last summer. “These are good.” He placed them on the huge bookshelf that covered most of one wall. “So are these.” He picked up two more.

“I know.”

“You read a lot?”

“Yep,” Celia said. “It takes me away from here.”

“Exactly.” He grinned. It was a real smile this time, way different than the fake ones.

Celia smiled back. “I loved in that one when they go on the long Appalachian Trail hike.” She pointed to the thick book in his left hand.

“And how that mountain lion follows them and you just know they are doomed,” Demetri said.

“And you think it’s going to try to eat them, but then it becomes their friend and protects them,” Celia added.

They talked about the various books in whispered voices as the thudding continued across the ceiling. Talking about books with Demetri felt the same as reading them. Slowly, Celia started to feel less and less freaked out.

“You know, you can stay here,” Celia said. “If your parents are away like mine and you’re alone. Or if you’re in some kind of trouble. If whoever is up there is violent.” She pointed at the roof. “When my parents get back, they’ll help you.”

Demetri flinched and looked toward the door. He seemed scared of her, for the second time.

“I should go now.”

“What about . . . ?” Celia pointed upward.

Both of them listened for a long moment. There hadn’t been any thuds in a while.

“I am certain it is safer out there than in here. Thank you for giving me shelter, Celia. It was very kind. And despite everything, it was nice to meet you.”

Demetri stood and made a funny little bow, the kind her grandpa might have done.

Celia didn’t want him to leave. She wanted to talk about more books and maybe go on a walk with him to explore the shaken city. Even if he lied and didn’t make sense half the time, she liked him, despite how weird he was. Maybe his strangeness was part of why she liked him so much. She got up and gave him a mocking curtsy in return. Her ankle twisted over a fallen book, and she fell toward him.

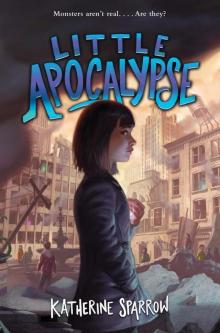

Little Apocalypse

Little Apocalypse