- Home

- Katherine Sparrow

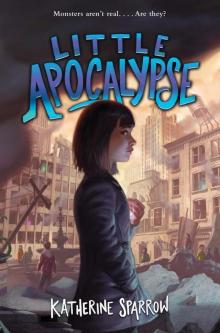

Little Apocalypse

Little Apocalypse Read online

Dedication

For Elijah, the boy who held fast

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Before the Beginning

1. Everything Fell Down

2. The Dream Girl

3. Everything Is Only Going to Get Worse

4. Living With Wolves

5. Lost Hope

6. More and More Complicated

7. Shouldn’t Be Real

8. They Can Smell Fear

9. Just a Girl

10. Breathe

11. Nothing Could Hurt Her

12. The Last One Anyone Should Trust

13. Fortune Favors the Bold

14. Interrogate, Intimidate

15. Who Unites Them

16. And the Next Will Hiss

17. Something Strange

18. Rainbows and Unicorns

19. Like a Nobody

20. The Girl Who Decides

21. Artificial Love

22. My Mind Cannot Make a Memory of You

23. The Last Bit of Warmth

24. Intrepid Heroes

25. The Second Rule

26. Filled With Plague

27. The Dialectics of Magic

28. Fascinating Creature

29. Obsessed With You

30. Like Flying

31. Silent Words

32. Trouble

33. The Victim

34. The Worst Monster

35. The Best Adventure

36. A Thousand Shades of Black

37. The Desire to Destroy

38. A Deluge of Fire

39. The Unlucky One

After the End

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Before the Beginning

The sad boy sat on the curb with his head covered in a knit hat, even though it was a hot day. He kept his face turned toward the gutter, staring at the brown trickle of water that ran into the sewage drain. With his arms wrapped around his belly, he took up as little space as possible and looked like he was crying, even though there weren’t any tears.

He took some braided shoelaces out of his pocket, closed his eyes, and murmured something as he fed the rope into the drain. He stood up and took a red yo-yo out of his pocket. He pulsed it a couple of times before sitting down and looking at the drain some more.

Celia stood across the street watching him. I should know him, she thought, but didn’t know why. She watched him for a full minute before deciding to cross the street and talk to him. She didn’t know what she would say to him.

Maybe she would tell him that he looked like the picture of how she’d felt ever since she’d moved to this city, left all her friends behind, and started going to the worst middle school ever. Or maybe she would pull off her own shoelaces and throw them into the drain in solidarity. Or what about just sitting down next to him? He might look at her and smile. She’d say something stupid, and he would think it was funny. Then he would teach her a couple of yo-yo tricks, and she would show him how to make origami cranes out of napkins. They’d spend the day exploring all the places in a city that no one ever notices: crumbly staircases, alleys full of broken furniture, and rooftops where birds roosted.

Celia stepped out into the road, ready for all that to happen, but a horn honked and a bus rushed by. The boy was gone by the time she crossed the street.

She didn’t think about the sad boy again—didn’t even know she’d made a memory of him—until the night that was the beginning and end of most things, four months later.

1

Everything Fell Down

“I can stay home if you want me to.” Celia’s mom ran a hand through her frizzy hair.

“I’ll be fine. I’ve been babysitting for two years. I can babysit myself for the weekend,” Celia said.

Celia’s mom rubbed the crease between her eyebrows as she looked out their bay window at the maze of cars and people on the street below. “Grandma’s probably going to get over the flu as soon as I get there. It’s just that at her age . . . and she’s been sick for two weeks.”

“Grandma needs you more than I do.” Celia reminded her mom of everything she already knew.

“And your father would cancel his trip; it’s just that—”

“That he has a new job and he can’t. I know. But one question? If a stranger offers me candy, I should take it, right? Especially if he’s in a van without windows?”

“You got it, kid.” Her mom winked at her.

“Nothing bad will happen while you’re gone. I promise.” Celia plopped down on their faded orange couch and surveyed the colorful mess of her living room.

“We’ll go on a road trip next weekend to make up for it. We’ll stop off at every roadside diner and eat every kind of pie from here to wherever we end up, okay? We’ll have fun. Promise.”

“Yeah. Fun.” Celia looked out the window at the gray day and tried to remember what fun felt like.

Her mom crossed the floral carpet and sat down on the couch. She slung an arm around Celia’s shoulders. “You know I love you and that you are an amazing kid. Everything will get better. You’ll make great friends soon. All the kids at your school are suckers for not hanging out with you.”

“So true.” I wish we’d never had to move here, Celia thought. I hate it here and I don’t know how to make friends. I’m shorter than everyone else and everything I wear is wrong and every time I talk to anyone they just ignore me or are mean. But she didn’t say any of that, because it wasn’t her parents’ fault. They’d lost their teaching jobs at the University of Portland because of budget cuts, and when they’d been offered jobs at South Youngstown Community College, it was that or flipping burgers. Her parents always said that in academia, you had to go where the jobs were. End of story.

“Bill?” her mom yelled.

“What?” Celia’s dad came out of the kitchen wearing a Kiss the Cook apron.

“Can you believe our daughter is old enough to stay home alone?”

“Are we still talking about this?” Her dad held a greasy spatula in one hand and a glass of wine in the other.

“I’ll worry about her all weekend.”

“That’s our job. But Celia’s thirteen. We’ll call her and text her and she’ll be fine.” He glanced at the living room wall full of framed pictures of their family: Celia grinning with her front teeth missing. Celia riding a bike with her mom. Everyone laughing on a boat last summer. “We’ll write up a list of rules that Celia will follow while we’re gone, and you’ll promise to follow them, right, kid?”

“Of course,” Celia said. Her life here was so boring that she probably wouldn’t even have a chance to break one rule while they were gone.

“I’ll miss you, even for just a couple of days.” Her mom hugged her.

Her dad hugged her too, and for a moment Celia’s sadness went away.

Her parents left in the middle of the day on Friday. Celia got out of school and walked behind some kids from her grade. She imagined running up to them and talking. Maybe she could tell them her favorite joke. What’s brown and sticky? They could think she was going to say something gross, and then laugh when she answered, A stick. Or maybe she could agree with them that biology was so dumb. Only, how could anyone not love biology and how weird and amazing the natural world was? And anyway, it wouldn’t matter what she said to them. Celia had spent months trying to be nice to kids at her school, and everyone was only mean back.

She hoisted up her backpack and followed the flow of people wearing long wool coats who stomped down the street, barking into their cell phones and glaring at the world. Portland was

the same size as Youngstown, but everything felt different here. Everyone moved faster and smiled less. Maybe because it was on the East Coast and an island, so everyone felt cold all the time? Maybe because it was farther north and that meant less sunshine and more grumpiness?

When Celia got home from school, she stepped into her empty apartment and took off her backpack and her coat, and then she shrugged off all the crappy things that had happened at school that day. No one had wanted to pair up with her in PE. She’d eaten lunch alone at the edge of a long table full of kids who ignored her. Then her English teacher had read aloud the essay she’d written on ethics while kids rolled their eyes and sent texts to everyone but her. People used to like me, she thought. It wasn’t like she’d had a best friend, but there had always been kids to hang out with in Portland. She’d gone to the same school, ever since kindergarten, and didn’t remember how she’d made friends: she’d just always had them. There had to be some better way to be the new girl, but Celia didn’t know how. Someday soon something had to change though, right? She would find a friend. Just one. That would make all the difference. It had been a long four months.

Celia put on her warmest flannel pajamas and went into her parents’ room to slip on her mom’s fuzzy slippers. She swung the closet door open and glimpsed herself in the full-length mirror. Her straight brown hair ended just below her ears and her bangs covered her forehead in a straight line. No one else at school had stupid bangs like that. Sadness covered her face.

She went into the kitchen to microwave a mac-and-cheese dinner. The typed list of rules her parents had left sat on the kitchen counter, along with two crisp twenty-dollar bills. The list was single-spaced and seven pages long.

1. Celia will not pet stray dogs, or bring home any cats, and if she finds a snake in the toilet like that documentary about Florida, she will flush it.

2. Celia will not open the door to any salesmen.

3. Celia will not do any drugs, even if the other kids promise they are super fun.

She read through it all and imagined them writing the list late last night with the hope that it would keep her safe, like a magic spell made of paper and ink.

Celia called her mom and told her that everything was fine, that school was great, and that she was going to watch action movies with girl heroes one after another until she got sleepy. She hung up and snuggled on the couch beneath a pile of soft blankets that smelled like cedar as she turned the first movie on. She watched those girls on-screen and wondered what it would be like to wear shiny clothes and always know the right thing to do. It would feel like the opposite of me, she thought, as she stumbled into bed and drifted off to sleep.

Motion shook her. The bedside lamp wobbled back and forth before crashing to the ground. It took a moment for Celia’s eyes to adjust to the darkness: a moment before she saw it wasn’t just her bed, but all four walls that shook. Books flew off the shelf. What were you supposed to do in an earthquake, again? She’d been through a million earthquake drills at her school in Portland. You were supposed to get under your desk, but there was no desk in her bedroom, or anything else to hide under. And there weren’t supposed to be earthquakes on the East Coast, were there?

Celia slid out of bed and crawled over the undulating floor to the window. A full moon lit the city, and the road moved like ripples in a pond. It felt like the world had turned to water, and her apartment was a ship at sea. Down on the street, chunks of building crashed to the ground. Cracks ran up a concrete wall. Windows broke. Celia looked up at her ceiling and watched cracks grow in the plaster. Her room smelled like dust. The world shook and shook.

Then, like magic, the world went still again. A moment later the blunt sounds of chaos—yelling, barking dogs, sirens—came through her window.

Celia sat on the floor amid the fallen books. Her arms and legs felt shivery and numb. That was huge, she thought. A huge earthquake. And I’m all alone. What would Mom and Dad do if they were here?

She righted the bedside lamp with shaking hands and tried to turn it on. Nothing. Same with the light switch. She walked through darkness to the phone in the kitchen. She started dialing her grandma’s number before noticing there was no dial tone. She searched for the cell phone next, and found it plugged into the socket near the toaster, surrounded by shards of a broken wine glass. There were no bars, and it beeped strangely when she tried to call out.

Celia moved slowly to her parents’ room, stepping over broken, half-seen things in the darkness. She rooted under their bed until she found the two flashlights in the emergency kit. She clicked them on, and two bright beams lit up the darkness. The light felt like a small miracle.

Celia searched every room in the apartment to make sure there weren’t any holes in the floor, or any walls about to fall down. Vases, pieces of paper, and broken picture frames lay scattered everywhere.

“Everything is going to be okay,” she whispered, and hated the sound of her fluttery voice in the empty room. She said it again and again, until she sounded strong. Through the front door, she heard her neighbors talking in the hallway. Celia pulled jeans on over her pajama bottoms before opening the front door.

Dozens of flashlights danced over the beige walls of the hallway.

“Anyone hurt?” a man called out. “I know CPR and first aid.” He stood in his doorway, wrapped up in a thick bathrobe.

Down the hall, another door opened. “We have candles, anyone need candles?”

“Or canned food? We have extra. No telling how long the electricity will be out.”

More doors opened, and more people offered help. Across the hall the old Hungarian woman who didn’t speak English and hardly ever left her apartment peeked out. Celia walked over to her and handed her one of the flashlights.

The woman’s cheeks crinkled into a smile. She patted Celia’s hand, murmuring something Celia didn’t understand before closing the door again.

“Where are your parents?” someone said behind her.

Celia turned around and looked up. The man in the bathrobe stood near her. “Are you alone?”

7. Don’t let strangers know you’re home alone.

“My dad is looking for our emergency lanterns: he thinks he left them somewhere near the pepper spray and baseball bat he keeps near his bed,” Celia lied. The most dangerous thing in their apartment was the sharp chef’s knife her father used when cooking dinner. Celia shone her flashlight in the man’s face until he went away.

Celia swept her light up and down the hall, like a lot of people were doing. Nothing looked broken or dangerous. She was just about to go back to her apartment, lock the door, and hide beneath a mountain of blankets when her flashlight skittered across some kids going through the door that led to the roof access. There were six of them, and they all wore worn pants and patched hoodies. One turned toward her light, and just before he lifted his arm to shield his eyes, Celia recognized him. It was the sad boy. The shoelace-and-yo-yo boy. He wore the same knit cap, which made more sense now that it was winter. As he frowned and squinted into the beam of the flashlight, Celia had the feeling all over again that she wanted to know him. He turned and ran up the stairs. The other kids followed.

Who would run up to the roof after an earthquake? Celia thought. Where were their parents? Didn’t they care?

Celia went back to her apartment and closed the door behind her. In the quiet, she could hear the stomp of footsteps overhead. What were they doing up there, in the middle of the night? Did the sad boy live in her building? Why hadn’t she seen him around?

9. Celia will not go gallivanting into the night.

But . . . there had been an earthquake. Maybe those kids needed help and were all alone, just like she was. Maybe their apartments were ruined and they needed a place to stay or something. Maybe it would be good to go make sure everyone was okay. Besides, she was getting creeped out in her dark apartment, all alone.

Celia slipped out of her apartment to go find the sad boy.

2<

br />

The Dream Girl

The padlock lay broken on the top step that led to the roof. A cold breeze blew in through the half-open door, and beyond it, moonlight lit the cold world.

Celia peered out of the doorway and saw the sad boy surrounded by a circle of kids in the middle of the roof. They wore hats or had the hoods of their sweatshirts pulled over their heads. Their clothes were baggy and they wore clunky shoes, like none of them could afford anything that fit right. The kids stood in a circle and held hands. There was something strange about them, something wrong, but the longer Celia stared at them, the more she had no idea what it might be.

Celia opened the door a couple of inches wider. The sad boy raised his hands and said something Celia couldn’t make out. He threw his yo-yo forward and did a complicated trick before it flowed back into his hand. The others swayed from side to side, raised their hands, and said something back to him. Sirens from the earthquake drowned out whatever words they said. Some of them were hunched over and had shaggy hair poking out of their hoods. Others bounced on their toes and had toothy smiles that stretched across their shadowed faces. In the moonlight, Celia couldn’t make out more details than that.

The door made an audible squeak as Celia pushed it all the way open and stepped onto the gravelly roof. The kids froze. All eyes turned to her. She pulled her coat around her and shoved her hands into her pockets.

“Hey,” Celia called out. The whiteness of her breath curled up into the night air. “Is everyone okay up here?”

The sad boy snapped his yo-yo up into his hand. He stared at her with his hard-angled face as he frowned and pulled his knit cap lower on his head. For a second, his eyes caught the moonlight and glowed. A couple of the other kids took a step toward her. One of them smiled with a mouth full of crooked teeth.

“Go. Now,” the sad boy said to his friends and pointed to some large pipes jutting out of the roof.

“There’s no law against saying hello,” a girl said.

“Go,” the sad boy said more forcefully.

The kids turned and ran away from Celia, moving in unison like a flock of birds. One of their hoods blew off and showed wild, spiky hair. They disappeared behind the pipes on the far side of the roof.

Little Apocalypse

Little Apocalypse